A common strategy employed in both primary and secondary school phases by teachers who are seeking to enhance their students’ independent learning skills lies in asking the youngsters to research an area that is of particular interest to them.

In addition to developing abilities associated with inquiry, students gain valuable practice in the traditional literacies of reading and writing, and given that the learners have the freedom to make their own decisions with regard to what they will investigate, levels of motivation are likely to be high.

In some instances, inspiration for the project will not come from the teacher personally; rather, the work will form an essential part of a wider course or, in the case of the Extended Project qualification offered in many schools at post-16, lead directly to a formal qualification.

The tasks of choosing an overall topic, isolating an issue for coverage and then framing this focus in an appropriate research question are challenging for many learners, and the decisions they make can have far-reaching consequences in the work that follows.

The selection of a certain topic may be revealed to have been unwise if it becomes apparent subsequently that there is insufficient high-quality information available or the problematic nature of the research question may only come to light if, after weighing the evidence they have collected, the student struggles to reach a convincing conclusion.

Of course, in most projects there are constraints that inhibit the selection decisions students can make and so prevent an entirely free choice being available.

Most notably, the area must be a viable one for research; it has to be possible to satisfy the appropriate assessment criteria when undertaking the work involved; teachers may add an ethical dimension, too, stipulating that the area should be socially acceptable.

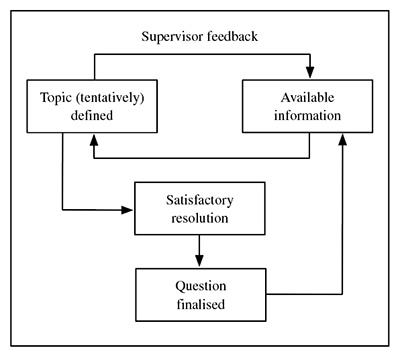

In recent years, I have developed a good practice model for topic identification, question formulation and information collection (reproduced below), which I share with my Extended Project students at the start of their projects.

The sixth-formers are required to design and carry out an independent research project on any subject of their choosing.

The study culminates in a 5,000-word essay and a presentation to staff and the other members of the Extended Project cohort. The model provides a means of helping the students to structure their activities, ensure a sense of purpose and work towards a clear end-state.

Good choice: A good practice model to facilitate topic selection, question formulation and information collection for projects

Each student must begin with an idea that excites them. While some talk animatedly of a particular subject immediately “jumping out” at them as soon as they have been briefed on the task, more often it is a case of students defining and then refining an area for investigation while exploring pertinent literature.

For sixth-formers, initial inspiration may come from reading an outline of a university course that they aspire to study.

Whatever the origin of the individual’s idea, reading is crucial in helping them to gain an understanding of the issues inherent in the chosen area, the extent of the information that pertains to them, and the quality of the relevant source material.

The student should conceive of the processes of topic identification and information exploration as not merely intertwined but mutually dependent, until they reach a state of satisfaction.

In short, they begin with an initial idea that they know will develop, collect information pertaining to it and use the discoveries they make as a result of reading this material to hone their topic.

Several iterations of the topic definition–information collection loop may need to take place before an adequate resolution emerges and from this position the student should be able, with help, to arrive at their final research question.

It is important that any model circulated to guide the learners specifically highlights the assistance that will be available from a teacher, supervisor or other form of advisor, such as the school librarian. The model shown here reflects the fact that, in the Extended Project, such an adult is on hand to lend support throughout the process.

Once the student has progressed to the stage where the research question has been confirmed, the main phase of information collection can take place. Unless the individual has changed their thinking very significantly, their information-finding activities are likely to become focused on one or more aspects of the original topic, with perhaps the addition of a particular perspective.

As well as investigating new sources, the student will revisit certain information and read it with greater rigour but will also probably discard some of the early material they gathered as it will now seem peripheral to what has become the real territory of interest.

Since the Extended Project demands that students document their research processes in full, I have often encouraged the learners to annotate the model. It can be helpful to issue paper copies of the structure, with the diagram in the centre of a sheet and plenty of surrounding space for students to record their developing observations on their topic and the material they have consulted.

Some have opted to show their various iterations of the topic definition–information collection loop in different coloured inks. Notes may also be added to indicate how satisfaction was eventually achieved at a particular stage; the definitive research question may be stated and some insight given as to the key sources intended to be used in the main phase of information collection.

Students who, at least initially, find it easier to represent their thinking diagrammatically than in prose often welcome the freedom that this approach offers before formalising their writing in the more structured logbook entries required in the Extended Project.

The model that has been the subject of this article does not, of course, address the whole of the research process, it concentrates on the early stages that many youngsters find especially problematic. Teachers may wish to extend its territory to embrace, for example, the essay-writing phase.

Although the version that has been offered here was developed for use with sixth form Extended Project students, it is entirely possible that, with appropriate adjustments, the diagram may be employed in other situations where students undertake prolonged independent learning projects.

The greatest benefits may well be felt at upper secondary level when the work involved is detailed and unfolds over a period of weeks or even months, but it is not inconceivable that younger learners will also benefit from adopting it. The use of a more pictorial design, with students responding by setting down their reactions via thought and speech bubbles, quickly comes to mind in this context.

- Dr Andrew K Shenton is curriculum and resource support at Monkseaton High School in Whitley Bay and a former lecturer at Northumbria University.

Further information

Dr Shenton has previously co-written a SecEd article on delivering the Extended Project. See Delivering an effective Extended Project, SecEd, April 2016: http://bit.ly/2mOSYh3