I often get asked what I mean when I say inclusion. The word can mean different things to different people: at the local authority, it might be about diminishing exclusions or SEN tribunals, CEOs of MATs might think about data and grades of cohorts, principals might think about budgets, and classroom teachers might think about stress.

They all think about plenty of other things as well of course and no one person is a stereotype – but then that is what I think when I consider the word inclusion: “We are all different really and that’s a good thing.”

However, there is one common teaching approach that epitomises SEND inclusion but which is often overlooked as part of inclusive approaches to teaching and learning: working in groups.

Of course, group work also has the potential for a Lord of Flies-type hell for students. And because it has so much potential for good and for damage, Sara Alston and I have dedicated an entire chapter to it in our forthcoming book. Here follows a summary of our advice.

It can go either way

Think about the more vulnerable students in your classroom. They could experience group work as either fantastic or awful:

- Group work is heaven: I belong, I have friends, my voice is worthy, I feel safe to try...

- Group work is hell: I don’t belong, I have no friends, my voice is not worthy, I don’t feel safe to try...

There are actually a heck of a lot of benefits and disadvantages...

The benefits of group work

It is perfectly human to feel that it is easier and nicer to work with a friend or in a group. We have people to bounce ideas off and the shared momentum can enable us to achieve the unexpected.

In other words, we human social beings also learn socially. We could write a whole book about this but I am sure you can easily grasp this notion – it is natural to learn in groups.

Indeed, many professions (and even the teaching profession sometimes) rely on group participation. Consequently, it can be argued that developing the ability to work with others is a core life-skill.

Furthermore, the need for group work in the classroom is clear. Not only is it a vital skill, but it provides variety and is an opportunity for children to learn from each other. The majority of children enjoy it. And, let’s be honest, it produces less marking.

Group work is an opportunity to promote and build inclusion within the classroom. It can provide an opportunity for children to work with different people and develop an understanding of each other’s and their own strengths and difficulties.

We want children to be active in exploring and learning for themselves. Groups provide a way of doing this without the direct guidance of the teacher. Groups are also ways for children to learn core skills, such as listening, presenting, arguing effectively and compassionately, team-work and so on.

The challenges of group work

Group work can induce anxiety – sometimes severely. It can leave children with a deep sense of failure and a raw sense of their own shortcomings.

Often, what happens in groups can be cited by students with anxiety weeks later as being the cause of their on-going mental health challenges around falling asleep or “facing others”.

It does not help that, for the teacher, groups are too difficult to “police”. To operate well in a group requires skills that need explicit teaching: both academic and social. For those who do not find working with others easy, working as part of a group could be asking them to do two things that they find difficult at the same time: engaging in academic learning and using their social skills.

Working with others can make children’s difficulties more visible both to themselves and others. The word might be “exposing”. When they are working on their own, those who struggle to read or write can mask and hide this from the majority of the class. When they are forced to work in a group, their difficulties are brought to the fore and put on show for others to see.

Group work might lead to ghetto-ising or reinforcing stereotypes and status. It is all too easy to put children in groups on the basis of where they sit in the class, so they work in groups with those sitting in their immediate vicinity. However, it is likely that your seating plan is based on ability and/or friendships. These are people that the children would normally work with and often socialise with. But that does not mean that they are the best people for them to work with for a particular task.

Getting the balance right

The key with group work is to balance the academic demands and the social needs. The greater the academic demand that we are making of a child, the lower we should make the social demands, and vice-versa.

If we are asking the child to tackle new material or learning in an area which they find particularly difficult, we should minimise the social demands by allowing them to work on their own or in a very small group. Equally when the learning is something that they feel confident with, we can increase the social demand.

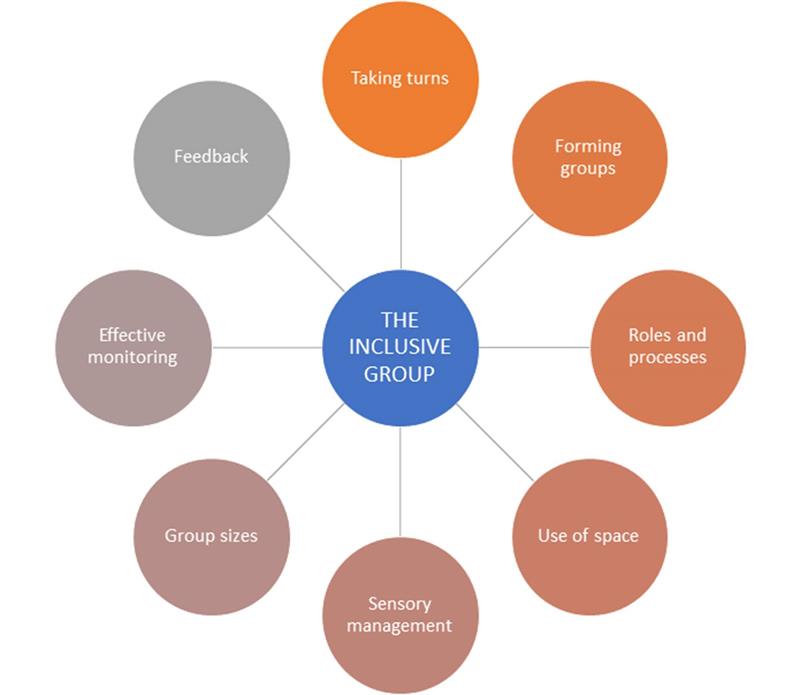

The following diagram shows us some of the factors that we should think about in making inclusive groups work in practice for all children.

Inclusive group work: Factors that we should think about in making inclusive groups work in practice for all children

Here are some tips for getting these factors working in an easy and doable way:

- Consider friendships groups: It is worth periodically asking children who they want to work with, ideally written down so others do not see. The answers are often surprising and illuminating. You could also allow the children to choose the group.

- Ensure all the children understand that they are part of the group by giving them some kind of badge.

- Supporting turn-taking is a skill that needs explicit teaching. Children need to develop not only the skills to let each other have a turn, but to listen and respond to what others say.

- Group roles: The basic idea is to allocate each child a specific role within the group. For example, a chair to make sure everyone gets to speak, a record-keeper or scribe, resource-gatherer, spokesperson, time-keeper.

- Establish a process for group work by providing a clear structure (e.g. Dr Edward de Bono’s thinking hats). It will make group work easier to understand and follow for many children, including those with SEND. It is very helpful to make these processes visual so that the whole group can see how they are working through the process and how they are moving from one stage to the next. This increases children’s sense of control and understanding of the group.

- Use all the space available so the groups are able to spread out. Though moving furniture can create anxieties and sensory issues about change, it can create more space. If the groups are spread over a greater space, it reduces sensory issues.

- Pre-warn the children when group work activities are planned, so that they come to the lesson with an awareness of the changed expectations. If this is not possible, give them time to adjust to and process the expectations before you start the activity. Be prepared to allow for fidgeting and fiddling to support children to deal with any change of setting.

- When looking to develop group work skills, start with smaller groups and move to larger groups slowly. Also focus on more structured tasks where the children can follow a clear structure to support them to work though the activity.

- Put the children in groups before you give them the task.

- Provide a prompt for the task.

- Let children attempt to solve issues before you get involved. This is always a difficult balance. You do not want groups or individuals to become overwhelmed, disheartened or disengaged, so it is very tempting to jump in to provide support for a group as soon as you identify that they are struggling or off-task.

Concluding thoughts

Group work skills cannot be picked up by osmosis and observing others alone. They need to be taught, made explicit and discussed. For children to develop the skills and benefit from the strategies discussed above, they need to develop a degree of metacognition about working in a group so that they evaluate not just the academic learning they achieved from the learning activity, but also focus on and consider the social learning.

There is one factor which stretches above and beyond all I have mentioned – something that sits behind the very nature of SEN in the traditional sense is the recognition that “I am somehow different”.

For a child, this can translate into: “I am good or bad.” Even for teachers: better students and less good students.

The judgement pervades the very idea of SEN. There are few remedies to this imposed, manufactured predicament. The most effective is through working in a group: all other doubts, differences and self-judgement can be resolved through peer supportive work.

We all know from personal experience and from children who we know that they can thrive when they have a good friend or peer group. This is the phenomenon at play. Validation from another and safety is precisely what a child can get from working in a group.

- Daniel Sobel is founder of Inclusion Expert, which provides SEND, Pupil Premium and looked-after children reviews, training and support. You can find all his articles for SecEd on our website via http://bit.ly/2jwoKP8

- Sara Alston is an experienced SENCO who also works as an SEND and safeguarding consultant and trainer at Inclusion Expert.