Always growing, always learning, – Kilgarth School’s mission statement encapsulates its approach to education in four simple words. The phrase is woven into the fabric of the school and forms part of an eye-catching tree mural (pictured, right) that greets visitors as they walk through the main entrance.

Kilgarth is a secondary school in Birkenhead, Merseyside for boys aged 11 to 16 who experience social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) difficulties. Housed in a single-storey building, in an area of deprivation and with little outside space, it is one of the most go-ahead schools in the country.

In recent years, Ofsted has judged the school to be outstanding in all areas, teaching staff have won a host of prestigious teaching awards, and virtually every pupil goes into education, employment or training at the age of 16. Much to the school’s delight, a year 11 boy recently transitioned back into a mainstream school – the first for several years.

KiIgarth is so determined that students should aspire to achieve great things that it asked scores of famous names to offer the boys their words of wisdom. The school then published a book featuring the responses it received from stars like Johnny Depp, Hugh Jackman, John Humphrys and Miranda Hart.

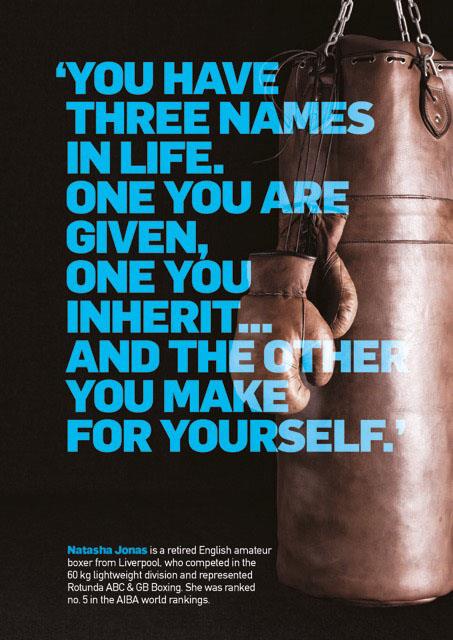

Inspiration: An example of the words of

encouragement pupils at Kilgarth School

were sent by a range of actors, sports people

and others

When Ofsted inspectors visited the 55-pupil school in 2015 they were glowing in their praise. They highlighted the fact that the pupils, who have a wide range of complex needs, such as ADHD, autism, foetal alcohol syndrome, attachment disorder and moderate learning difficulties, make remarkable progress.

Inspectors said: “From very low starting points, pupils who experience significant barriers to their learning, including those eligible for Pupil Premium funding, make good and often outstanding progress in English, mathematics and other subjects.”

Executive headteacher Steven Baker was delighted by the Ofsted report but remembers thinking: “Right, what next?”

Far from resting on their laurels, he and the Kilgarth team were determined to keep on improving. “You can’t sit still – it’s not fair on the boys,” said Mr Baker.

He continued: “What we try and do is give the boys a welcoming environment, a safe school. On the whole it works really well but some boys are very hard to reach. We are having increasingly complex young people joining us and there’s an increase in the number of challenges we are facing on a daily basis, whether it’s hunger, poverty, austerity measures or policy changes from central government. We’ve got to keep evolving to meet the needs of these boys – because if we don’t I don’t know who will.

“The boys here are a remarkable bunch. They’re great, but it’s heartbreaking when you see some of the areas they live in and the poverty and the challenges they have in their lives – and it’s only going to get harder.”

Kilgarth’s latest initiative is radical to say the least. Concerned that sanctioning the pupils was not helping them to modify challenging behaviour and was not tackling its root cause, Mr Baker and head of school Mick Simpson decided to abolish punishment altogether.

“We’ve always been non-confrontational – it’s part of our DNA,” said Mr Baker. “The removal of sanctions and the focus on social skills was a natural evolution. It was the next step for us.”

Mr Baker and Mr Simpson make a formidable team. Mr Baker originally worked as a forensic anthropologist – he spent two months in Bosnia, exhuming war graves and examining human remains for the International Criminal Court investigation into the massacre at Srebrenica. He is a member of Remembering Srebrenica’s North West regional board, helping to develop social cohesion and raise awareness of the Srebrenica genocide.

The experience brought him face-to-face with the very worst of humanity and when he returned to the UK he trained as a teacher, determined to work with disadvantaged children and make a difference. He became head of Kilgarth in 2011 and is now executive headteacher of Kilgarth and nearby Gilbrook School, a special primary school for girls and boys aged five to 11 with SEMH difficulties.

Mr Simpson worked in mainstream schools until eight years ago. He arrived at Kilgarth as assistant head and won the silver award in the science teacher of the year category at the 2015 Teaching Awards. Now head of school, he is also the proud owner of Otis, Kilgarth’s much-loved school therapy dog, who provides support for pupils at times of emotional pressure.

Mr Simpson raised the possibility of removing sanctions at the school after noticing that the same boys were turning up for detention time and time again.

“I started to ask why we were sanctioning pupils when it wasn’t affecting their behavioural choices,” he said. “I started to have conversations with people I thought would be like-minded, saying that I wasn’t sure that the sanctions were working – but what could we put in their place?”

Around the same time, Mr Baker was invited to join the advisory board of Learnus, a think-tank that brings together educators and those who specialise in the study of the brain, the mind and behaviour. He got talking to Dr Alice Jones, senior lecturer and director of the Unit of School and Family Studies at Goldsmiths, University of London, about her research on conduct disorder and childhood behaviour and discussed the idea of removing sanctions altogether.

“All of a sudden the scientific validity for what I felt started to become apparent,” said Mr Simpson, “that for a variety of reasons, sanctions do not work for some parts of our school population.”

The reasons for this are manifold. Some pupils have an “inhibited fear response” and do not make an association between poor behaviour and adverse consequences, while others simply do not care.

The two men knew that in order for the initiative to work they had to get everyone involved on board – staff, governors, parents and the students themselves. The school also held a staff training day, where Dr Jones gave a detailed presentation about her research.

“She explained why sanctions don’t work, and what does work,” said Mr Simpson. “And what does work is reward. It works for some of the time for some people – if you get it right. So the trick was to design a system where we recognised good behaviour rather than recognised poor behaviour. We decided that the spotlight should be off the poor behaviour and firmly on the behaviours that we wanted to see as an institution.”

The new system, whereby sanctions were abolished and replaced by rewards for good behaviour, was launched in 2015, six weeks before the start of the summer holidays.

“We chose that time specifically because we thought ‘if this goes pear-shaped then we’ve got the summer holidays as a safety net’,” said Mr Simpson.

The system is still evolving but the reaction from pupils and parents has largely been positive and there has not been an increase in the most challenging behaviour. “It’s important that there is a breadth of rewards,” said Mr Simpson. “The most important reward as far as I’m concerned is praise. We recognise the behaviour that we want to see and praise it explicitly. So it’s not just saying ‘well done’. It’s saying ‘well done for smiling at me when you came in because that makes me feel good’. Or ‘well done for passing that person his pen. I love that because it’s being helpful and creates a good working environment’.”

Then there are daily rewards, ranging from a social activity, such as making a cup of tea and having a chat (the boys call it a “sit-off”), to playing sport or having a game on the XBox.

There are also more infrequent rewards, like certificates, prizes and trips. The boys gain points for effort and behaviour in every lesson and every time they reach a certain threshold they get a raffle ticket and their name goes into a draw. At the end of each term the staff draw out three prizes – two £25 prizes and a £100 prize.

In recent months the school has refined the system further, targeting the boys who think “I’d rather mess about now and not have a reward later” or “if I stay out of my lesson I’m not going to earn my social time but at least I’m not in maths”.

“We tackle that through something we call a PEL – a post-event learning opportunity,” said Mr Simpson. “We say ‘we’re not going to punish you but the amount of learning that is being missed can’t be acceptable in this school. We really care about you so if we see a pattern emerging of missed learning, not because you’re in crisis or there’s a problem, but because you can’t really be bothered, then we are going to extend the school day’.”

Now, instead of finishing school at the usual time of 2:30pm on Mondays, Kilgarth has extended the school day till 4:30pm.

“The boys who have been attending lessons the previous week still go home at the usual time but the boys who haven’t stay on,” said Mr Simpson.

“We say ‘this is not detention, this is lesson time, and what we are going to do is teach you the things that you’ve missed. You may not have engaged with the subject or you may feel you can’t do it, but we are going to empower you to succeed’. We take the opportunity to work with the students, re-equip them and as far as possible make sure they are in a place to engage with learning.”

The Kilgarth staff emphasise that these sessions are not punishments, although the boys make quips along the lines of: “That’s genius. You’ve found a way to punish us without saying it.”

“I tell them ‘no, from the bottom of my heart, this is not a punishment’,” said Mr Simpson. “This is an opportunity to right the things that aren’t going right in school, to address the disadvantage that you face in life and look to the future with more optimism.”

Interestingly, since the school introduced what the boys call “missed learning”, some pupils have asked: “Do you have to miss learning to stay behind? Can we stay anyway?”

The answer, of course, is “yes”. “We laud them and we are in the process of making arrangements for them,” said Mr Simpson. “Our staff are so excellent that for some of our students this is the nearest they get to a functioning, loving family – and so they stay behind just for them.”

Perhaps a word now should go to a former pupil’s mother, who wrote a poem about the impact Kilgarth has on the boys. Here are a few lines:

It builds back up what life’s torn down,

it nurtures as we grow.

It guides us in the right direction,

when wrong it tells us no.

It laughs at those who write us off

and proves the world it’s wrong.

Our heads hung low when we arrived,

our young backs bent by heavy loads.

We soon stand tall when we realise

this school is truly home.

How Kilgarth supports its staff

Executive headteacher Steven Baker is acutely aware of the need to support his staff, who work tirelessly in a challenging environment.

“We’ve got to look after staff because if they aren’t functioning 100 per cent there is going to be an impact on the children,” he said. “Everything here is people-centred and people-focused and we do a lot to support the emotional resilience of our staff.”

With that in mind he has introduced coaching at Kilgarth and Gilbrook. The staff are trained to support and guide each other in finding solutions to specific problems – through active listening, key questioning and encouraging colleagues to be solution-focused. Keen to ensure the coaching is not hierarchical in any way Mr Baker has been coached by an unqualified teacher and Mr Simpson by a teaching assistant.

Other innovations include taking part in research projects and encouraging CPD. Mr Baker has also developed a behaviour management training programme – “loosely based around neuroscience, the development of the brain in the teenage years and our non-confrontational approach” – and takes every opportunity to share his expertise with other schools.

- Emma Lee-Potter is a freelance education journalist

Further information

For more information about Remembering Srebrenica, go to www.srebrenica.org.uk