The figures – from 2016/17 – have been unearthed during an investigation by the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (Partridge et al, 2020).

The report warns that during the past five years, there has been a 60 per cent increase in the number of pupils permanently excluded from England’s schools.

It adds: “By 2017/18, the last school year for which data is available, there were – on average – 42 pupils expelled each school day.”

It presents qualitative and quantitative evidence – including data obtained by Freedom of Information requests – that pupils are being permanently excluded to artificially boost schools’ standing in league tables.

The study blames “perverse incentives” in the school accountability system, a narrowing of the curriculum, the trend of zero-tolerance approaches to behaviour, and a lack of funding to support the most vulnerable pupils, among other factors.

Its authors are urging Ofsted to grade schools “explicitly on how seriously they take inclusivity”. It also says there should be a greater role for councils in preventing this kind of off-rolling practice.

Freedom of Information requests made to all local authorities by the RSA found that in 2016/17, 7,719 permanent exclusions were made by England’s schools.

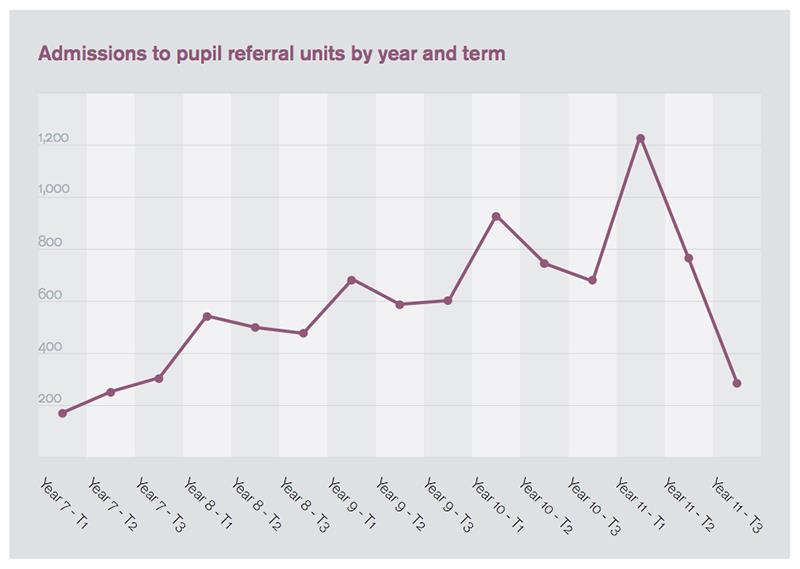

Of these, more than 1,200 pupils were admitted to pupil referral units in the first term of year 11 – the last point before a student’s exam results count towards a school’s performance. This compares to 763 in the second term of year 11. A further 676 students entered PRUs in the last term of year 10.

The report shows that admissions to PRUs slowly grow from under 200 in the first term of year 7 to the peak of more than 1,200 in year 11 before dramatically dropping (see graph below).

Suspicious spike: A graph from the Pinball Kids report shows how exclusions spike in the first term of year 11. From January in year 11 (term two), a pupil's exam results will count towards a school’s performance scores (Source: Partridge et al, 2020)

It states: “The peak is highest in year 11 and the numbers drop off definitively from the second term onwards, supporting the notion that pupils are moved from mainstream schools into alternative provision before their exam results count towards the school’s performance scores.”

The most common reason for exclusion is “persistent disruptive behaviour” and the report says that certain groups are “disproportionally represented in exclusions statistics”.

More likely to be excluded than their peers include children with SEND (six times more likely), those from poorer backgrounds (four times more likely), certain ethnic minority groups such as Black Caribbean (three times more likely), and those who have been in care (significantly more likely).

Furthermore, the report warns that these figures do not show the whole picture: “There is good reason to believe that a greater number of pupils than the figures suggest are leaving a school never to return: pupils who have not gone through an official exclusion process and are therefore not captured in the statistics, but have effectively been ‘removed’ from school.”

Last year, a report from the Education Policy Institute (EPI) warned that 49,100 students from the cohort set to have finished year 11 in 2017 disappeared from school rolls with no explanation given, the equivalent of one in 12 pupils or 8.1 per cent (Hutchinson & Crenna-Jennings, 2019; SecEd, 2019).

Part of the problem, the RSA concludes, is the risk of disengagement of some pupils in the face of a much more “rigorous” and narrow curriculum: “Many interviewees noted that the difficulties some pupils had in accessing the GCSE curriculum led to a sense of not being able achieve at school, resulting in disengagement which increases the risk of exclusion.”

Funding cuts and incredibly stretched budgets, including for SEND support, also meant that many schools struggled to meet the needs of their most vulnerable pupils, the report adds.

The authors also warn that a rise in “zero-tolerance” approaches to behaviour has led to minor misdemeanours being heavily punished. The report adds: “The rise in so called ‘zero tolerance’ behaviour policies is creating school environments where pupils are punished and ultimately excluded for incidents that could and should be managed within the mainstream school environment.”

Elsewhere, the accountability regime, including the Progress 8 measure introduced in 2015, is creating “perverse incentives” because excluding certain pupils can improve a school’s overall Progress 8 score: “This well-intentioned policy has inadvertently created an incentive for schools to exclude,” the report warns.

One headteacher told the researchers that current incentives make it “tempting to take routes to get Progress 8 scores”, another fighting special measures added: “It was so tempting sometimes to make children disappear.”

The RSA wants Ofsted to “reward headteachers for pursuing measures to ensure every pupil feels included and supported at school and so help prevent exclusions happening in the first place”.

It also calls on the, Department for Education to mandate that the date of and reason for all managed moves and transitions to home education are recorded on school information systems before pupils can be removed from the school roll.

The report asks, too, for wider change in the system to focus on inclusive relationships between staff and pupils, including professional pathways for pastoral staff.

Laura Partridge, associate director at the RSA and report lead author, said: “The number of disadvantaged pupils being excluded from school every day is alarming and should prompt urgent action. While wider social factors as a result of austerity have played a role, our research shows that the direct and indirect consequences of the accountability system are directly contributing to this rise.

“Pursuing perverse incentives, instead of prioritising quality teacher-pupil relationships, is having a hugely detrimental effect on the life chances of the most vulnerable pupils.

“Many schools are already doing great work, but this is becoming harder and harder to maintain under the current system, which is why Ofsted needs to reward schools that value inclusivity.

“But importantly, this isn’t just about Ofsted. Further investment is needed so that collectives of schools and public services can work preventatively to meet the needs of all pupils, thus reducing the need for that 'final resort' of exclusion.”

- Hutchinson & Crenna-Jennings: Unexplained pupil exits from schools: A growing problem? EPI, April 2019: http://bit.ly/2J7MKr8

- Partridge et al: Pinball kids, RSA, March 20209: www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/preventing-school-exclusions

- SecEd: Off-rolling: One in 12 students ‘disappeared’ from mainstream schools, May 2019: https://bit.ly/2wAFlwR