With rapidly rising pupil numbers, a current shortage of places in one-fifth of local authorities and high parental expectations, secondary school admissions are arguably about to come under even more of a spotlight than usual.

Demand has already risen

Nationally, pupil numbers in state secondary schools have risen by 69,000 since January 2013 and now stand at nearly 2.85 million (as of January 2018), the highest level since the start of the decade. Secondary school applications also rose by 83,000 between 2013 and 2018, a rise of 17 per cent.

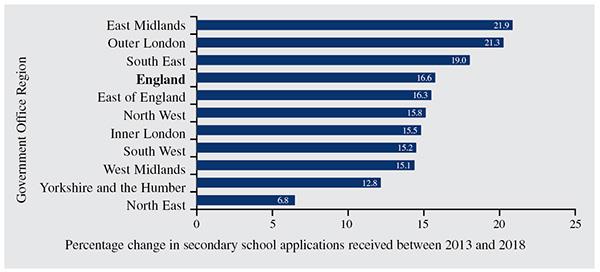

School applications data also shows that 96 per cent of local authorities had more applications in 2018 than they had five years previously. However, although most of the local authorities in England have seen some growth over this period, as Figure 1 shows, growth rates differed significantly by region.

Figure 1: Pupil numbers have risen in all regions, with some having larger increases than others

Too few places to meet demand

Some local authorities may already be feeling the impact of this rapidly rising demand. In January 2018, 29 local authorities, nearly one in five, received more secondary school applications from families who live in their borders than there were places available.

This is a sharp increase from January 2014, when only 17 local authorities had more secondary school applications than places.

The excess demand in these oversubscribed local authorities is also getting worse. In 2014, the 17 oversubscribed local authorities received 191 more applications on average than they had spaces available. However, in 2018, the 29 oversubscribed local authorities received an average of 234 more applications than places available.

The shortage of places is most acute in urban areas. In 2018, 27 of the 29 local authorities that were short on places were cities such as Birmingham, Nottingham and Bristol, and London boroughs – particularly outer London boroughs such as Greenwich, Ealing and Croydon.

In contrast, areas with a large surplus of places appear to be largely rural. In 2018, there were 14 local authorities which had more than 1,000 surplus places, which were largely rural counties such as North Yorkshire, Norfolk and Cumbria. These large surpluses in some areas appear to suggest problems with place planning at a regional or national level. A surplus of this magnitude could indicate that some rural schools are struggling to remain viable, and difficult decisions may be required to ensure school places are located in the areas where they are needed.

Rising competition?

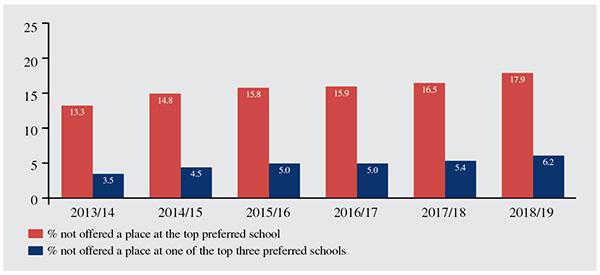

There has also been a steady increase in the proportion of families not getting a place at their most preferred school or a place in any one of their top three preferences.

Figure 2 shows the gradual increase in the percentage of families whose school preferences are not being met. As before there are big regional variations, with London worst affected. One in three families in London did not get their top preference in 2018, while about one in eight did not get any of their top three preferences.

Figure 2: More pupils are not being allocated a place at their preferred secondary schools

The number of appeals is rising

Over the last three years the number of families who have had an appeal heard about their secondary school allocation has also risen slightly. In 2015/16, the proportion of parents appealing secondary school allocations was 3.6 per cent, which rose to 4.1 per cent in 2017/18.

While part of this may be due to the rising secondary pupil numbers since 2015/16, it may also be an outcome of growing tensions caused by greater competition for places and falling percentages of families being allocated a place in any of their top preferred schools.

Demand set to rise further

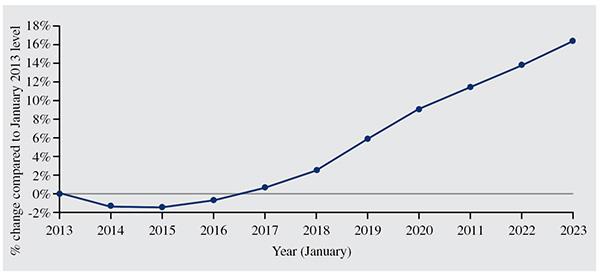

The supply and demand trends, along with a reduction in parental preferences being met, are particularly worrying as the Department for Education’s (DfE) own projections indicate that there will be an extra 376,000 pupils in the secondary school system by January 2023 compared to 2018 levels (see figure 3).

This is largely due to the increase in the live birth rate in England from around the early to late-2000s. Overall, secondary pupil numbers in January 2023 will be 16 per cent higher than 10 years earlier.

What can local authorities do?

As local authorities know how many children they have in their primary schools, it should be possible for them to accurately predict the number of places needed at secondary level in any given year well in advance and take action to create sufficient pupil places. Many local authorities will have already started to make plans to meet this growing demand for places, although knowing about the growing demand and having the ability to implement changes at sufficient speed can be a challenge.

There are several ways that the available secondary capacity in a local authority may be increased, each of which will have an impact on school leaders. A new free school could be opened, which depending on its size could bolster capacity significantly, albeit not for a few years as there are considerable steps to work through, from navigating the complex planning process and finding a suitable site to hiring sufficient numbers of new staff. While a new school adds capacity, it also increases competition to attract pupils, which may be an issue for any local schools which are judged by Ofsted to be underperforming.

Another lever that local authorities may seek to use, which can be quicker to implement, is to work with school and academy leaders to expand an existing school. Local authority schools or academies may agree to take on a bulge class for one or more years, or to increase the number of form classes in the school, or expand existing classes. The local authority will work with school leaders in their planning area to explore whether they have scope to expand to help meet this extra demand or whether they can take on extra pupils within their existing structures, all of which brings extra challenges.

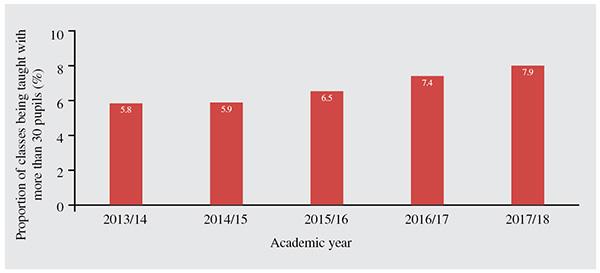

National data suggests that increasing secondary class sizes may already be happening as they average 1.1 pupils more than they did in 2013/14. Figure 4 shows that the number of classes with more than 30 pupils has also risen by 2.1 percentage points since 2013/14.

What does this mean for schools?

With secondary school places in England projected to continue to increase, and at an even faster rate than seen in the previous half decade, this could have a big impact on secondary schools. Without a considerable increase in places available in key areas, there could be yet more local authorities that do not have enough spaces to meet demand. This may lead to a rising number of families not receiving a place at one of their top preferred schools, increasing tension with parents and the unhappiness of pupils, who have to attend a secondary school they did not want.

There are also significant potential consequences for school leaders and teachers. School leaders may have to deal with more issues around reduced pupil engagement, more requests from parents seeking to move their child to/away from their school, and greater pupil mobility.

Teachers may be increasingly likely to teach in crowded schools or teach larger classes. Extra pupils, even if they can be accommodated in temporary classrooms, may put pressure on all school services, such as dining halls, sport facilities and pastoral care provision. These factors could have negative consequences for staff recruitment and retention, which may already be a problem area for the school.

So brace yourselves, as the next few years look likely to be challenging. It is important that the DfE looks urgently at how they can support local authorities and schools in areas where there are not enough school places to meet demand.

- Zoe Claymore is a researcher at the National Foundation for Educational Research.

NFER Research Insights

This article was published as part of SecEd’s NFER Research Insights series. A free pdf of the latest Research Insights best practice and advisory articles can be downloaded from the supplements page of this website: www.sec-ed.co.uk/supplements