Implementing a stretch and challenge model in your classroom requires teachers and students to recognise that learning should be difficult. This may seem like a pretty obvious statement to make but often, without recognising it, we set a limit on what we think students can do.

Stretch and challenge is knowing your students really, really well, through a combination of scrutinising a range of hard and soft data to enable us to make the best decisions when planning for students’ learning.

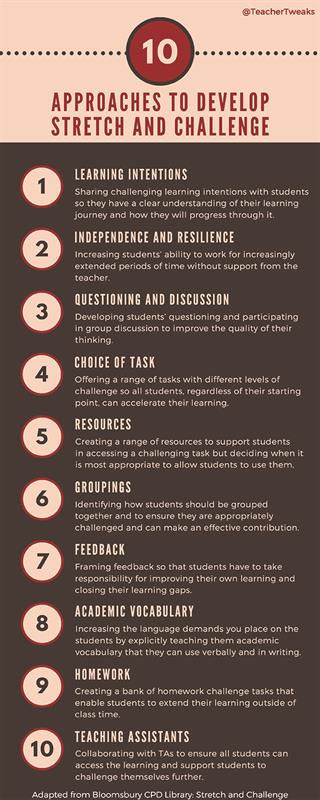

Once you’ve diagnosed your students’ strengths and barriers to learning, there are a whole host of options you can implement to raise the bar in your classroom.

The options discussed in this article all have one factor in common: a belief that all students can produce excellent work once they know what it looks like and are given appropriate tools and support to make it happen.

Learning intentions

First of all, let’s be absolutely clear: differentiated learning outcomes must be removed from all classrooms if a stretch and challenge model is to be embedded into everyday practice. You are signalling to students that you’ve made a decision that only a few can reach the top. If students see there is a choice of how much they will learn in a lesson, then it is too tempting for them to coast along doing the bare minimum.

Learning intentions are an integral part of communicating to your students that you expect all of them to think deeply every lesson. Rather than waste time getting students to copy down vague learning objectives and outcomes, move towards an enquiry question that will anchor the learning and everything the students do in a lesson or series of lessons to respond to the question posed by the teacher.

Professor Dylan Wiliam, in his book Embedding Formative Assessment, explains that students sharing, clarifying and understanding learning intentions is a key part of assessment for learning; those students who have a clear picture of their learning journey are more able to reflect on their progress over time and take responsibility for knowing how to move forward.

Independence, resilience and TAs

Ask any teacher what they want from their students and nearly all of them will say “I want them to be more independent”. In our quest to make students more independent, we have forgotten that they need to know an awful lot before they are ready to work independently. There is no real challenge posed if a student is told to go off and be independent if, once they get there, they don’t have the knowledge or skills to complete the task successfully.

The aim is to encourage students to work for extended periods of time without relying on the teacher’s constant input. Professor John Hattie, alongside Gregory Yates, in Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn, explore the difference between teachers as activators as opposed to teachers as facilitators.

Teachers as activators results in a much higher effect size; some of the key actions they take are setting up tasks with the goal of mastery learning and teaching students metacognitive strategies.

If students are going to work independently, then they need to have a clear goal in mind where the steps to success help students to judge how well they are working towards their goal.

Linked to this, they will need to be taught to think in specific ways so that, when they face difficulties, they can draw upon subject-specific strategies and questions to ask themselves to help them select the right domain of knowledge to complete a task.

Where a student has access to support from a teaching assistant, it is vital that the student doesn’t fall into the trap of learned helplessness. The teaching assistant’s role needs to be clearly defined. A well-deployed teaching assistant can encourage students who struggle to work independently by modelling the processes required to develop independence and resilience.

Teaching assistants can ensure that they work alongside students to get into the habit of chunking tasks down into clear steps for success, asking metacognitive questions and verbalising their thinking, which will lead to the creation of excellent work.

Questioning and discussion

Prof Hattie identifies classroom discussion, where students are given the opportunity to respond to challenging questions posed to them, as being integral to accelerating students’ learning.

Robin Alexander, in his book Towards Dialogic Teaching, highlights the over-reliance on IRF (initiation-response-feedback) in the British classroom. Much classroom discussion centres upon the teacher initiating discussion by asking a question, choosing a student to answer and then acknowledging whether the answer is correct.

This cycle is repeated several times with different students. Apart from the issue of how time-intensive this model is, there are two ways it obstructs challenge.

First, only a handful of students are forced to participate – those that are chosen by the teacher. Most students can be a bystander rather than an active participator. Second, it is the teacher who holds all of the power because they are the ones initiating the questions and deciding on the direction of the discussion.

One way of embedding a stretch and challenge model is to experiment with different ways of encouraging greater participation in discussion. The expectation should be that every student is required to think deeply and make a contribution to discussion.

In order for this to happen, set up a series of structured questions that require students to think hard and ensure students have enough time to grapple with the difficult concepts. Also make time for students to construct their own questions and pose them to their peers. Explicitly teach students how to construct different types of questions to generate engaging discussion.

Tasks, resources and groupings

For many years, stretch and challenge was seen as something for the “gifted and talented” group. Normally, it meant an extension task for those who finished their work early; however, the extension work often ended up being more of the same rather than requiring stretching students to think harder.

Setting up choice can be a tricky one to get right and, if done badly, can be detrimental to stretch and challenge if students choose less cognitively demanding tasks. Effectively incorporating choice means setting the bar high and expecting all students to produce excellent work but acknowledging the route to producing this work may be different depending on the students’ needs.

Teachers must think carefully about how a task is scaffolded and carefully selecting resources so all students can access the most challenging work. These resources may include worked examples, literacy scaffolds or graphic organisers. View other students as resources too; group work can prove a nightmare in the classroom if time is not given for students to learn how to operate effectively in a group – they won’t just be able to work together naturally. The best group work is when the cognitive demand of the task actually necessitates more than one student’s input.

Graham Nuthall’s research in The Hidden Lives of Learners found that most of the feedback students get is from their peers and that, alarmingly, 80 per cent of it is wrong! Moreover, for deep learning experiences to occur and be stored in their long-term memory, they need to be exposed to the information at least three times in different formats. Therefore, it is vital that when offering students choices they are held accountable for the work they produce.

Feedback

There can’t be a teacher on this planet who doesn’t know by now that feedback has a significant effect on students’ outcomes. Yet what isn’t as well promoted is that feedback can also have a negative impact on students. Ego-driven feedback, focusing on the student rather than the task, and grades rather than comments, leads to a decrease in student progress.

Feedback needs to be framed in such a way that it is clear to the student what their learning gaps are and how they can close them before moving onto new learning. Students are notoriously bad at acting upon the feedback given to them by their teachers. If students don’t respond to our feedback, then what’s the point in marking their work?

Another frustration teachers experience is when students hand in work that is just not up to standard due to carelessness or lack of effort. A classroom where stretch and challenge is embedded is one where students know the standard they are aiming for, actively seek out feedback to reach that standard, and have the tools to move their own learning forward by using this feedback to develop their knowledge, skills and understanding.

Prof Wiliam examines the importance of success criteria and pre-flight checklists in Embedding Formative Assessment. Ensure that success criteria for a piece of work makes clear to students how they can demonstrate excellent quality work.

Rather than setting a limit on what we think students can do by creating differentiated criteria, give all students the same criteria but make explicit to them how meeting the criteria becomes progressively more demanding.

Once students have attempted a piece of work, teach students how to use pre-flight checklists which ask students to check their own or a peer’s work against the criteria and highlight areas for development before handing in their very best effort.

Academic vocabulary

Varying levels of literacy is one of the most significant factors in how well a student will do at school. Since academic vocabulary knowledge is at the heart of being a good speaker, reader and writer, it is important that teachers dedicate enough time to explicitly teaching academic vocabulary in their subject areas to challenge students to express themselves with confidence.

Robert Marzano and Debra Pickering’s book, Building Academic Vocabulary, shares a structured approach to teaching academic vocabulary. Begin by providing a description of the word before asking students to create their own description and example in their own words. Using visuals to accompany the word as a memory cue helps students to remember the work.

Ensure that students engage with academic vocabulary on a regular basis through discussion, word games and vocabulary notebooks to consolidate knowledge. As well as Marzano and Pickering’s work, Doug Lemov in Teach Like A Champion has introduced two strategies that raise the language demands of students: Right is Right and Stretch It.

Combining these two techniques, the teacher’s expectations of the students is that a student has not finished until their response is 100 per cent accurate and they have developed their thinking using academic vocabulary and a range of examples. Rather than accepting students’ first responses, giving students an opportunity to practise their response through oral rehearsal results in much more sophisticated thinking.

Homework

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) Teaching and Learning Toolkit informs us that homework in secondary school can have a significant impact on student outcomes. Yet few schools have cracked the homework problem.

If truth be told, many of us can forget to set homework or set something rushed just to keep up with the homework timetable. It’s often the last thing we think about after we’ve planned our lessons. However, getting homework right makes such a difference to the challenge culture. The problem with classwork is that students often don’t have enough time to engage with a challenging task. Homework gives students greater freedom to demonstrate what they really know and produce quality work.

To get over the problem of setting homework for homework’s sake, an alternative is to create a Homework Challenge Bank featuring a range of tasks that require students to consolidate and master key concepts and apply their knowledge in different contexts. If students know that they are expected to complete a set number of the homework challenges by the end of the topic, then this stops the arbitrary setting of homework at inconvenient times.

A note of caution: sometimes students are given homework tasks that seem challenging because they require students to work independently on a project over an extended period of time. While these homework projects can be a lot of fun, many students struggle with such open-ended tasks. If students are producing a piece of homework over a sustained period of time, make sure they are provided with clear structure and steps to success so they can self-regulate. Finally, celebrate and showcase students’ homework as this will encourage students to keep challenging themselves as their efforts won’t have gone unnoticed.

Conclusion

Whatever approach you take, embedding a stretch and challenge model in your classroom takes time. Students may struggle at first with the increased demands placed upon them. However, if you stay resolute and communicate with students the changes you are making and the benefits these changes will bring, they will end up appreciating your high expectations of what they can achieve.

- Debbie Light is an advanced skills teacher and a deputy head in a London secondary school. She is the co-author of Lesson Planning Tweaks For Teachers and is one half of @TeacherTweaks. Her new book, Stretch and Challenge, from Bloomsbury Education is out now (ISBN: 9781472928405) priced £22.99.