Did you notice that 2015/16 was the Year of Fieldwork? For those involved, it was an exhilarating year of celebration – a joint effort between the Geographical Association (GA) and 26 other organisations, including the Field Studies Council, Ordnance Survey, the technology firm ESRI (UK) and the Royal Geographical Society/Institute of British Geographers.

Its principal aim was to promote the place of fieldwork in the curriculum, including to:

- Increase the opportunities for pupils of all ages to experience high-quality fieldwork.

- Support the integration of fieldwork into the school curriculum from primary to post-16.

- Raise awareness of the importance of fieldwork as a pedagogy and as a critical tool for geographers.

- Promote the benefits of fieldwork as a skill across a wide range of subject areas.

Fieldwork CPD for teachers was one of the most popular and high-impact activities during the year, with around 1,300 teachers attending fieldwork CPD events run by the GA alone.

However, the GA also conducted research into schools’ experience of implementing fieldwork. This is an important dimension of learning for a growing number of students, since geography has been one of the fastest-growing subjects at GCSE and A level in recent years, with nearly 40 per cent of GCSE candidates now taking the subject.

We surveyed schools over the summer term, just ahead of qualification changes which mean that the amount of fieldwork required for GCSE and A level is increased.

From September 2016, GCSE students are required to gain practical experience of at least two environments; A level students must undertake four days of fieldwork and complete their own independent investigation.

So the survey was an attempt to gauge the current “state of play” for fieldwork, in anticipation of the changes to come.

The results – from more than 250 schools – suggest that teachers are working hard to ensure fieldwork is an integral part of students’ geographical learning. More than 70 per cent provided local fieldwork in year 7 and 56 per cent did so in year 8. More than 55 per cent of schools included fieldwork in the form of day trips beyond the locality in years 9 and 10, and 76 per cent provided both one-day fieldwork and residential experiences.

Residential fieldwork experiences increased significantly in years 12 and 13. Comparisons with earlier, similar surveys stretching back over 20 years were particularly interesting.

Our 1996 results showed slightly more schools undertaking fieldwork in key stage 3, but significantly more (65 per cent against 55 per cent) doing so in year 10. So the amount of fieldwork within the geography curriculum appears to have declined and this trend will need to be reversed in order for the new requirements to be met.

Although the majority of respondents did indicate that they are planning to expand their GCSE and A level fieldwork provision in the future, far fewer acknowledged that, to prepare

A level students to be independent investigators, they will need to provide them with more fieldwork experiences in key stage 3.

A regular diet of fieldwork is needed throughout the secondary phase in order to build students’ knowledge of and skills in different approaches, as well as their confidence to work independently.

Going back to the 1996 survey – in that year we also found teachers predicting that fieldwork provision would increase in the future, whereas the opposite subsequently occurred.

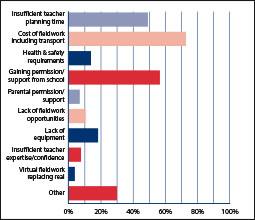

The reason for this disconnect is that there are on-going obstacles to fieldwork in schools, and the GA’s research identified many of these.

Although teachers also told us they continue to make the case for fieldwork and seek the support of parents and school leaders, they also reported that a “crowded curriculum” means schools are finding it increasingly difficult to find time during regular school hours for fieldwork.

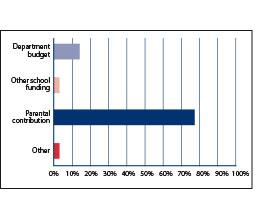

However, funding emerged as the chief obstacle to providing fieldwork, with many schools heavily dependent on parental contributions as the principle source of funds (see graph, below)

Barriers: The Geographical Association’s research revealed the main barriers to conducting geography fieldwork, and the main sources of funding for activities (above)

An equalities issue is immediately apparent. In the “age of austerity”, further work may be needed to ensure that our nationally increased expectations for fieldwork do not present a problem for schools and families in economically disadvantaged circumstances, or result in a situation where some students gain more or better fieldwork experiences by virtue of the school they attend, or the community in which they live.

Other issues emerged from schools’ responses, particularly a lack of professional skills and confidence. While teachers were happy to lead geography field excursions themselves, they relied increasingly on external providers as students progressed towards GCSE and A level.

The range of techniques teachers reported as using was relatively narrow, and little use was made of specialised equipment. Funding may once again be an issue here, with fairly obvious implications for the range of techniques students acquire during the course of their education if schools are unable to purchase appropriate technical equipment for gathering data in the field.

However, teacher expertise and confidence are equally relevant. Our research suggested many teachers continue to rely on a few straightforward fieldwork techniques, such as devising questionnaires.

Fewer teachers reported using more innovative, complex or ambitious techniques, which suggests a need for subject specialist CPD to be made even more widely available than was made possible during the Year of Fieldwork.

This finding substantiates the conclusion reached by the independent geography panel of the A Level Content Advisory Board, which was charged by the Department for Education with designing the new A level.

In its final report (Report of the ALCAB Panel on Geography, p32) the panel recommended that “investment in appropriate CPD and accompanying resources will be essential for the effective delivery of the new qualifications”.

In the absence of a central government push to implement the new fieldwork requirements, schools will need to look for other sources of funding and support.

A range of organisations and charities are active in this regard. For example, the Frederick Soddy Trust provides support for expeditions and fieldwork which includes the “study of the whole life of an area with major emphasis on the human community”. Five awards of between £250 and £500 are made each year.

The Field Studies Council (FSC) also operates a number of bursaries, enabling individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds to take part in FSC curriculum-focused courses with their school.

Finally, teachers and students can access a wide range of free support materials for planning and undertaking fieldwork online, including from the FSC’s Geography Fieldwork website and the Geographical Association.

- Alan Kinder is chief executive of the Geographical Association.

The GA report

Headlines from the GA’s Secondary Fieldwork Survey (conducted summer 2016) are available in the autumn issue of GA Magazine for GA members (http://bit.ly/2fap7Ax). The full report is due to be published in early in 2017.

References

- Report of the ALCAB Panel on Geography, The A Level Content Advisory Board, July 2014: https://alcab.org.uk/reports/

- The Frederick Soddy Trust: www.soddy.org

- Field Studies Council bursaries: www.field-studies-council.org/about/the-fsc-bursary-fund.aspx

- Geography Fieldwork (FSC website): www.geography-fieldwork.org

- Fieldwork resources from the Geographical Association: www.geography.org.uk/resources/fieldwork/fieldworkideasandresources/#top