The ability to reflect on and construct meaning from personal experiences is a key feature of high-quality learning today, not only in terms of that of students in schools but also with respect to that of adults at university and in the workplace.

These processes tend not come entirely naturally to young people, however, and in any programme of education that relies heavily on such reflection much depends on the skill of the facilitator in making available appropriate opportunities and on putting in place effective frameworks for promoting it.

The Extended Project and customer journey mapping

Reflection is an especially significant part of the Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) that is offered to sixth-formers in many schools. Essentially, the EPQ is a large-scale independent learning assignment, in which the candidate’s record of their research processes is as important as the end product.

Each student nominates their own topic for investigation, frames a suitable research question and then sets about answering it using an evidence-based approach that may draw on both published information and personally collected data.

In most cases at my own school, Monkseaton High, candidates work towards the creation of a 5,000-word essay. They must submit, too, a diary or “logbook”, showing, from a chronological standpoint, how their project has developed and, ultimately, how they plan and deliver a presentation to staff and the rest of the EPQ group.

Marks are specifically allocated to reflection and the process permeates all four assessment objectives. There are various opportunities for students to demonstrate the required levels of reflection during the course, notably when making their logbook entries, but one of the candidates’ last major chances is in the presentation.

The framework for stimulating reflection that I have developed is based on customer journey mapping (CJM), which has been applied for years in a range of tertiary businesses. Managers typically employ CJM in order to gain insight into the needs and preferences of users when they exploit a particular service, with the ultimate aim of improving the client experience. It has been practised, for example, in libraries to enable providers to understand the perspectives of patrons.

The time of implementation

My original inclination was to introduce a CJM approach during the taught phase of the EPQ, at the beginning of the course, but I eventually decided against it. As the candidates are already required to document their ideas in the logbook throughout the duration of their studies, I feared that an additional demand that they construct CJMs while their projects were taking place might be excessive.

There was the danger, too, that the importance of this element may be lost in the students’ minds amid all the other advice and instructions that were being offered to them at the time.

I was also concerned that as under the assessment arrangements marks could not easily be made available for the map, candidates may struggle to see the point of producing one. Very often, I encourage my charges to prepare well structured essay plans as they are contemplating writing their 5,000-word documents. My words frequently fall on deaf ears, however, with many learners being understandably reluctant to spend time on work that will not be directly assessed. I felt sure that a similar problem would arise in relation to CJM.

Finally, making a stipulation that they must create such a map could lead to the EPQ becoming, in the students’ eyes, merely another exercise in jumping through a series of teacher-determined hoops, rather than being a genuine independent learning project as I intended.

After much consideration, then, I decided on recommending near the end of the learners’ studies that they construct a CJM, so that they could reflect on their EPQ experiences in retrospect and then either refer in their presentations to what had emerged from their review or report their thoughts on the final page of their logbook.

I realised that this timing was not perfect, as insights that the students had gained along the way may be lost by this point but I reasoned that if they were sufficiently important they were bound to be remembered and learners who were constructing a CJM in the last few weeks of the EPQ course would be well placed to understand their individual experiences in a proper perspective.

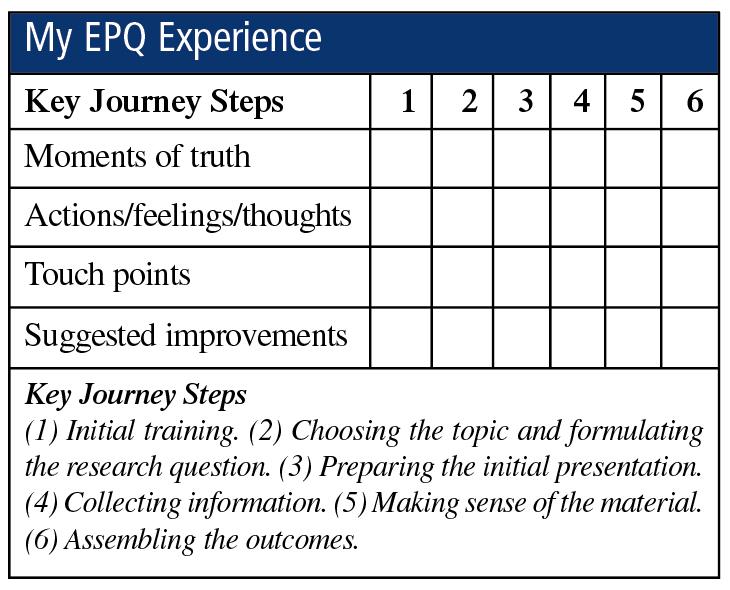

Furthermore, the mapping exercise would afford an opportunity for the candidates to view their projects holistically. My favoured strategy lay in using a larger version of the grid shown below to stimulate the students’ reactions to appropriate prompts.

Reflections: A simplified version of the customer journey mapping proforma

I gave each learner an editable, Microsoft Word version, thereby allowing them the freedom to adjust the sizes of the rows and columns depending on what they had to say and alter labels so that they better addressed particular issues with which that student was most concerned.

Some candidates, however, opted to work with a paper version of A3 size or even larger. The prompts within my grid were based on those stated within the CJM form developed by the health-oriented Cumbria Learning and Improvement Collaborative, and are as follows:

- Key journey steps – what I regarded as the main phases within the EPQ process. If students believed other stages within the course were more significant to them personally, they were at liberty to change those specified in the table.

- Moments of truth – major points in the individual’s EPQ journey where they paused and evaluated the experience or made a crucial decision.

- Actions, feelings, thoughts – what the candidate did and their affective and cognitive responses.

- Touch points – instances where the student had some form of interaction with school staff, e.g. through scheduled personal tutorials or approaches they made proactively to their supervisor or a subject specialist.

- Suggested improvements – situations where, with hindsight, the learner would have done something differently.

Format

I emphasised to the students that their CJM did not have to take tabular form. If they felt more comfortable thinking in pictures than in text, they might prefer to produce a diagram, with their responses in terms of the five strands shown in a different colour.

The diagram might be drawn by hand or be electronically generated. I also indicated that in their presentations students could reproduce their map as a handout, show an electronic version as a slide or speak in front of an especially large version that they might show on a flipchart. A few candidates have opted to use a blank copy of my CJM grid to guide the process of reflection that they undertook more spontaneously during their talk.

Whatever is decided, a student’s main priorities in terms of CJM should lie in making it apparent to the assessors that detailed reflection has taken place on their part and in helping the audience to develop a feel for the EPQ as that individual has experienced it.

Final thoughts

Although some youngsters, even at sixth-form level, struggle to apply an abstract framework to their own situation, many of my EPQ candidates made effective and original use of the headings I offered them in the grid.

One girl, for example, reacted to the actions, feelings, thoughts prompt by producing a line graph that showed how her levels of confidence and certainty had fluctuated over the course of her project.

The EPQ would seem ideally suited to CJM treatment which, my experience tells me, tends to be most successful in fostering reflection in situations when the “three Ps” are particularly apparent, i.e. when:

- The work is prolonged, taking place over a period of weeks or even months.

- The study is heavily process-oriented.

- The project consists of pronounced phases that are readily identified by the learner.

It may well be possible for the teacher to construct a single proforma that can be utilised in a variety of independent learning situations. Clearly, where this is intended, the key journey steps need to be represented generically.

Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process Model (Kuhlthau, 1989) may prove valuable inspiration in this context. Here the phases are those of task initiation, topic selection, information exploration, focus formulation, information collection, and presentation.

Alternatively, the stages within my own national curriculum-based framework may be helpful. This approach would lead to the definition of the following steps: initiating the inquiry, planning the action to follow, implementing – acquiring material for scrutiny, constructing meaning, communicating to others and, finally, considering and assessing. Other models of information literacy present elements that can equally easily be either adopted or at least adapted to serve as key journey steps.

Ostensibly, the purpose to which CJM has been put in the work reported in this article is very different from its conventional use in research to evaluate services from the client’s viewpoint with the aim of improving them.

Although my piece has concentrated on the potential of CJM for encouraging student reflection, it is highly likely that once these insights become apparent to those responsible for the teaching programme involved, they can prompt the educators to adjust the work for future groups in such a way as to address problems and issues that the learners’ maps have revealed.

- Dr Andrew K Shenton is curriculum and resource support at Monkseaton High School in Whitley Bay and a former lecturer at Northumbria University.

Further information

Information Search Process: A Summary of Research and Implications for School Library Media Programs, Professor Carol C Kuhlthau, SLMQ Volume 18, Number 1, Fall 1989: http://bit.ly/2vGbhi9