The idea of “mastery” has been traditionally associated with teaching and learning in mathematics, based on models originating from methodology used internationally.

Mastery learning breaks subject matter and learning content into units with clearly specified objectives, which are pursued until they are achieved.

Mastery teaching encourages pupils to learn to redraft and improve their own work, equipping them with a deep understanding of their learning. Learners work through each block of content in a series of sequential steps.

A mastery approach to learning and teaching, as opposed to a more traditional differentiated approach, can equally be applied across the curriculum. Here follows some ideas and tips for developing mastery.

Make sure that the learning journey is clear

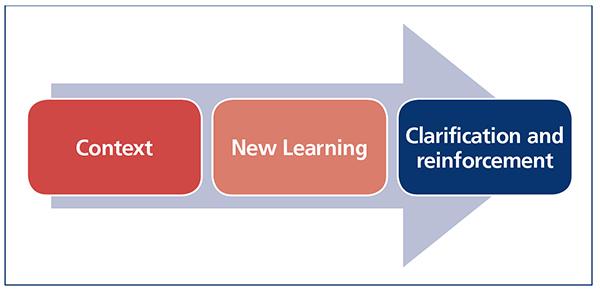

Mastery connects best to a learning sequence or journey. A clear learning journey enables our pupils to engage with the context for learning first, i.e. how the learning relates to their life experience, the real world or something else concrete that the pupil can identify with.

This makes it easier to then teach new learning since the pupil has something concrete on which to add new ideas and concepts. In turn, this enables teachers to identify which learning requires the greatest exemplification and focus.

Mastery map: Context and reinforcement are crucial aspects on the road to mastery

Ensure all learning begins with the concrete

The best learning, in every context – classroom-based, skills-based, learning outside the curriculum, learning at home – will usually start from a point of personal experience. For us all to learn effectively we need to make sense of new learning by putting it into the context of what we already know and understand.

Generate a sense of purpose and audience

As well as context, our pupils need to know the purpose of the new learning – “why” are we asking our pupils to learn this or acquire this skill? What learning is it based on? Where will this learning lead? In other words, how does this learning fit into “the big picture”? This helps to provide the “why” of learning.

Make the learning visible across the environment

Not only do your pupils need to be clear about what, why and how they are learning, they also need to know that learning takes place in a variety of contexts – classroom, across our schools, in our communities, at home etc. This should be evidenced visually since most of us learn even better with visual reinforcement. By showing our pupils that learning is all around us at all times, it gives them reasons to deepen their learning and understanding.

Create a common language for ‘mastery’

If we want our pupils to engage effectively with mastery, they need to engage with the language of mastery and this language needs to be consistent across our schools. Examples of how we can do this include:

- The consistent use of agreed question stems for mastery (some good examples may be found at https://goo.gl/XEqKw8).

- Prompt cards for mastery (see https://goo.gl/KFprXd for some ideas).

- Mastery learning displays: make classroom displays interactive and engaging by displaying pupil work that models the stages of mastery learning, evidences the stages of success, and includes clear teacher feedback explaining how to improve.

Model mastery responses with children

In order to master mastery, our pupils need to know what “mastered learning” or “good learning” looks like – so model it and show them.

Evaluating their own learning

Plan multiple opportunities for pupils to evaluate their own learning and that of others. Pupils’ engagement in their own learning and progress is key to the quality of that learning and progress.

If we want our pupils to master their learning, we must create meaningful opportunities for peer and self-assessment. However, make sure that the skills of peer and self-assessment are taught, just as you would teach any other skill. To make peer and self-assessment work for both you and your pupils:

- Have clear assessment criteria.

- Develop the assessment criteria with students.

- Use anonymous examples of work.

- Vary the type of work they assess.

- Model responses so they know what good peer assessment can look like.

- Allow time to respond.

- Provide feedback on their peer/self-assessments so that they can improve their own assessment skills.

Aim high and accept nothing less than excellent

Since mastery is about stretching our pupils’ thinking and learning, we need to ensure our expectations are high for our pupils.

So, how do we do this? Here are some simple classroom strategies to try:

- No opt out. Although a lesson might start with a student not being able to answer a question, by the end of the learning, they should be able to answer that question as often as possible and in as many different ways as possible. Opting out is never an option.

- Know what ‘correct’ means. Set and defend a high standard of correctness in your classroom. Use questioning techniques like “pose, pause, pounce, bounce” to develop partially correct answers into the best answers you can get from your pupils – and never accept partially correct answers as a finishing point, only a starting point.

- Stretch it. The learning journey does not end with a right answer; reward right answers with follow-up questions that extend knowledge and test for reliability. This technique is especially important for differentiating teaching and ensuring the learning needs of our most able learners are met.

- Mind their language. It’s not just what pupils say that matters but how they communicate it. To succeed, pupils must take their knowledge and express it using good sentence structure, syntax and the vocabulary of your subject. Teach them how to do this and don’t accept second best.

- Don’t apologise for expecting the best. Sometimes the way we talk about expectations inadvertently lowers them. If we’re not on guard, we can unwittingly apologise for teaching worthy content and even for the students themselves. Try to imagine the most ‘‘boring’’ content (to you) that you could teach and script the first five minutes of your lesson plan in which you find a way to make it exciting and engaging to students.

Ensure learning is fun

Following on from our previous point, our pupils will master their learning more quickly and confidently if they enjoy their learning, since all of us learn best when we are relaxed, safe and engaged in what we are doing. So, make learning fun by:

- Discovering new things together – learn with your pupils and be part of the learning journey.

- Incorporating mystery into your lessons – highlight the weird, the unusual and the unique, and start your lesson with objectives presented as questions or puzzles to be solved rather than statements.

- Showing you care – make them laugh and feel good by using humour with them to show you care.

- Participating in projects – be part of the learning as well as the teacher. Show pupils what you are learning at the moment and what you find difficult or challenging. Ask them to teach you.

- Avoiding “going through the motions” – it is easy to fall into a pattern of teaching the same thing in the same way every time. A simple idea is to fragment your lesson into a sequence of learning activities and then start at different points in the sequence.

- Flipping your lessons – flipping your lessons will help you avoid boring in-class activities. If students watch short video clips or listen to podcasts or correct their own homework the night before, you can spend the lesson focusing on deeper learning. Everyone will appreciate the chance to reflect on, instead of repeating, the material.

- Reviewing – but not repeating – material. It’s important for learning and memory to review new material regularly and to integrate it into the bigger picture shaped by old material, but don’t just repeat the new learning without its context since this will hinder the pupils’ ability to learn.

- Making learning active. Passive teaching makes for dull learning, so keep learning active. This doesn’t necessarily mean asking more questions, but it does require a stylistic shift whereby you and your students are actively exchanging ideas – not just responding to them.

- Try being a student again. Take a seat in the class and let your pupils teach you for some of the lesson. Let pupils grade you on examples of projects or presentations you have prepared for them based on specification criteria.

- Enjoying yourself. People with high confidence, i.e. people we respect and listen to, tend to have one important trait in common: they enjoy themselves. Quite literally.

Conclusion

Essentially, mastery refers to understanding, on a deep level, the taught curriculum. Mastery in learning should not be all smoke and mirrors, it is just about broader cognitive stretch, as opposed to racing through curriculum content.

- Steve Burnage has experience leading challenging inner city and urban secondary schools. He now works as a freelance trainer, consultant and author for staff development, strategic development, performance management and coaching and mentoring. Visit www.simplyinset.co.uk and read his previous articles for SecEd, including his previous CPD workshop overviews, at http://bit.ly/2u1KW9e