“I define connection as the energy that exists between people when they feel seen, heard, and valued; when they can give and receive without judgement; and when they derive sustenance and strength from the relationship.”

Dr Brené Brown, research professor, University of Houston

When a student’s life is characterised by transience and instability, establishing positive new relationships can be testing.

Moving from a school setting which was, for me, distinguished by positive student-teacher relationships, which posed no real challenge to construct and maintain, left me with distorted confidence and a sense of failure. I was working diligently and deliberately to foster trust among staff but was failing to make headway with my students.

Every educator understands the importance of building positive relationships with students. To quote the Australian Society for Evidence-based Teaching: “To a large extent, the nature of your relationship with your students dictates the impact that you have on them. If you want to have a positive and lasting difference on your kids, you need to forge productive teacher student relationships.”

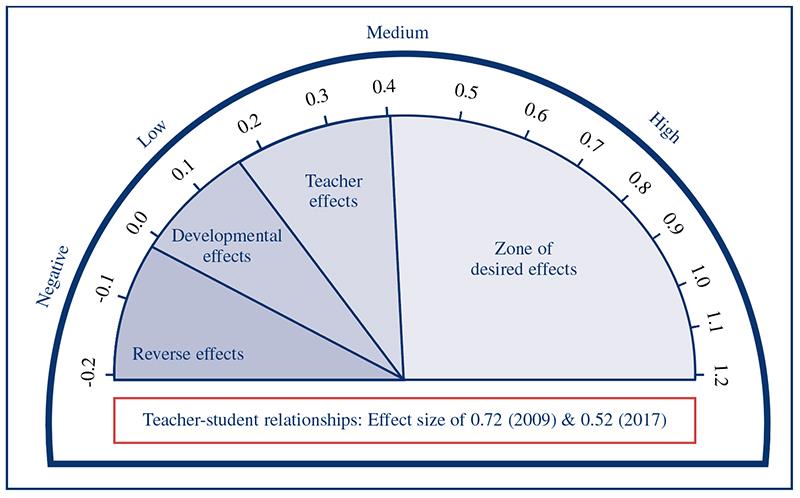

Professor John Hattie’s Visible Learning research in 2009 suggested that the quality and nature of the relationships you have with your students has a larger effect on their results and outcomes than socio-economic status, professional development or reading programmes (see diagram, below). He states: “It is teachers who have created positive teacher student relationships that are more likely to have the above average effects on student achievement.”

It is not that the other factors don’t have an impact on students’ lives, but rather that your relationships with students matter more. With this in mind, failing to establish positive relationships early on in term one felt suffocating and crippling for me and my students.

Effective: Professor John Hattie’s 2009 Visible Learning research ranked the effect sizes of influences on student outcomes. In 2009, he ranked strong teacher-student relationships with an impact of 0.72. Further research has seen this effect size reduced to 0.52. The average effect size is 0.4. Prof Hattie’s current ranking of 256 influences can be found at http://bit.ly/2uaWMiU

I have felt the impact of positive relationships in other school settings – and have never found it difficult to build them. Yet in my new school setting, I felt a resistance, an unwillingness to connect from my students.

As a teacher, head of English and assistant headteacher it was essential for me to find a way to secure positive teacher-student relationships.

I began to make conscious behavioural choices to build trust. Some of my students lives are marked by betrayal: they’ve been let down by the adults in their lives. I began to apply some of the strategies I use as a leader to build trust with colleagues, with my students as well.

In her article, How the best leaders build trust, Lolly Daskall recommends eight strategies to employ with adults and I have focused on deploying four of these in particular:

1, Character

Daskall suggests that “when people experience your character, they will trust you”. She recognises that consistency is crucial: “When you consistently do the right thing, whether you feel like it or not, when your actions match your words, you give people evidence of your character.”

Being authentic and genuine and sincere creates an environment where students can do great things in safety and without fear; trust can blossom.

2, Genuine care

I also showed my students that I genuinely care. Daskall states that “trusted leaders love people; they value connection and seeing others succeed”. The same is true of children.

The teachers’ job is made so special and so rewarding because of the relationships, the connections. The students I work with are beautifully and heartbreakingly complex and are, neurologically speaking, wired to feel before they think.

When my students appeared defiant, resistant and oppositional, I had to recognise that they were presenting their stress response. In Brains in Pain Cannot Learn (2016), Lori Desautels explains that “we are all neurobiologically wired for social connection and attachment to others”.

It was hugely challenging in the first term at my new school as I was craving the positive teacher-student relationships I’d had in my previous school – it was hard and left me feel like I was failing.

3, Competence

Daskall believes that “when people view you as competent, they will trust you”. This was about finding a balance between showing the students that they could trust me – that I knew what I was doing (despite not knowing where the photocopier was yet...) – but also having the fortitude to admit when I didn’t know something (I love being asked the type of questions only children can ask, where the only bona fide response is: “I don’t know”).

Occasionally making tactical mistakes was important too – creating an environment which valued mistakes and failures as part of the learning process. I planned brilliant and meaningful learning opportunities for the students every lesson.

4, Consistency

The last principle from Daskall that I used with my students is consistency: “When people see you act with consistency, they will trust you.” I have worked with leaders before who have responded with inconsistency and unpredictability, which not only made trust difficult, but bred fear.

In Beyond Discipline (1996), Alfie Kohn claims that “children are more likely to be respectful when important adults in their lives respect them”. He continues: “They are more likely to care about others if they know they are cared about.”

Slowly but surely

I have seen and felt and heard my strategies work: previously unanswered salutations on duty are now being responded to verbally and with smiles. Students are saying hello in the corridors.

Whereas previously I’ve had to insist on a “Miss” added to the “yes” during the register, the students now willingly respond with enthusiasm and kindness.

While standing at the front of the exam hall at the start of a year 11 mock, one of my toughest students gave me a smile and a small nervous wave. Three of my other year 11s came to find me after their literature mock to tell me how it had gone. One of my year 9s drew me a picture at lunchtime and left it on my desk.

These seemingly insignificant moments have the ability to unleash my students’ potential to be brilliant, to be exceptional and – as sense of social connection is one of our fundamental human needs – these moments have felt colossal and absolutely magnificent.

Forming, storming, norming, performing

You can’t expect a new team to perform well when it first comes together. One of my new colleagues impressed upon me the importance of utilising the friction between my previous setting and my new one to make changes and improvements.

Bruce Tuckman’s Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing model (see online) explores possible stages that new teams go through on the path to collegiate cohesion and high performance. I’d argue that I’ve been going through a similar process with my students too. Finding a balance between building trust and forming the new team while also making changes was quite delicate.

- Forming: getting to know your new team (and students) can be challenging; your values align and you begin to work towards a common goal. Trust is grown.

- Storming: despite having negative connotations, this stage shouldn’t be unwelcome. Because trust is being developed, team members are more willing to share their perspective and opinion, which can create conflict. Having worked with leaders I’ve struggled to trust and where I have felt mute and invisible, I have consciously welcomed different views and perspectives in this new role – I’ve sought them out. There is nothing more toxic or damaging than feeling insignificant within a team.

- Norming: now that criticism and conflicting views are considered to be constructive and task-oriented, the team can cooperate: establishing rules, sharing common values, building and maintaining high standards – the team is developing its own identity, informed by everyone in it. Everyone should be able to recognise themselves in the team and feel that they are a part of something special.

- Performing: trust, when “developed and leveraged ... has the potential to create unparalleled success and prosperity in every dimension of life” (The Speed of Trust, Stephen Covey, 2006). Teams can begin to perform and excel, working towards a common, shared purpose.

Learning how to “establish, grow, extend and restore trust” (Covey, 2006) has helped me settle into my new school and new role – but it hasn’t been easy. Working in this new school setting in my new role has felt like both the most challenging work I’ve done and the most important.

- Caroline Sherwood is assistant head and head of English at Isca Academy in Exeter. To read her previous articles in SecEd, go to http://bit.ly/2UbukrO

Further information

- What everyone needs to know about high-performance, teacher-student relationships, The Australian Society for Evidence-based Teaching: http://bit.ly/2VQuHZV

- Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses on achievement, Professor John Hattie, 2009: https://visible-learning.org

- How the best leaders build trust, Lolly Daskall: http://bit.ly/2Tyhjgc