Benfield School is in the east end of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is a smaller than an average secondary and the proportion of Pupil Premium students is much higher than the national average. The proportion of students who are disabled or who have SEN is also much higher than average.

Benfield has an additionally resourced centre for young people with medical or physical disabilities and the Cherrywood Centre, an additionally resourced provision for young people with social communication difficulties, including autism.

In March, Cherrywood won a national Autism Professionals Award for Inspirational Educational Provision. When Cherrywood opened in September 2013, we were very keen that students were full and equal members of the school, rather than a separate setting within the same building. So drawing on our work and experiences, I offer below 10 ways in which mainstream schools can support their learners with autism.

Effective home-school communication

In a mainstream school there are many demands of a young person that require them to remember information and communicate it home. This can add a lot of pressure and cause anxiety about remembering – or distress when something is forgotten.

Young people with autism struggle with communication. Impairment of social communication forms an essential part of the diagnosis process and therefore it should not be assumed that learners with autism are able to go home and communicate effectively with parents or carers.

At Cherrywood, a home-school folder system is in place. Anything that needs to go home or to come back to school goes in the folder. Folders are checked each morning by staff and parents are asked to check folders each evening at home.

The folders also contain home-school contact books. These allow daily communication between staff in school and parents/carers at home. This allows staff to let home know what sort of day a young person has had – and vice-versa.

Peer understanding

Supportive peers can make a huge difference to young people, whether they have autism or not. Some young people with autism may only have subtle difficulties in social communication whereas others may behave in ways which seem very unusual – such as flapping, unusual ways of walking or challenging behaviour. It would be very easy for such behaviour to become a source of humour or ridicule and it is important that the school as a whole celebrates individuality.

We have established an Autism Ambassador Programme where mainstream peers attend training sessions to learn more about autism. Having young people who have increased knowledge and understanding of autism hopefully results in knowledge being passed across peers, rather than only cascading downwards from adults. Students also attend assemblies about autism and staff from Cherrywood deliver autism awareness lessons during the year.

I have worked with autistic pupils in mainstream schools for some years now and students have always responded well to learning about autism and being trusted with a sensitive subject. Mainstream peers can view autism, and disability in general, as taboo. Once pupils are encouraged to ask questions, I find they have many. Workshops with peers can also be valuable in addressing misconceptions.

Change

Young people with autism can find change extremely difficult to manage. This does not mean that changes should never happen, changes are unavoidable in a mainstream school – and in life in general. It is important, however, that staff understand the underlying reasons behind the reliance on routine. Young people with autism can struggle to make sense of a busy confusing world, resulting in a strong preference for predictability and sameness.

When staff are aware of upcoming events or changes, it is helpful if they let autistic learners know, either directly or through discussion with staff who work closely with the young person. Anxiety often stems from uncertainty about what will happen and can present as challenging behaviour. It is important to prepare students as much as possible.

As young people with autism tend to be visual learners, change can best be explained in writing and pictures. Small details tend to be important – what will happen, who is going, which members of staff are going, how will they get there?

I am a big believer in the young person having something they can take away and refer to should they need to. Having an explanation in writing also means that staff can support the young person during the event – bringing their attention to a particular part of the document if necessary.

Learning environment

Sensory sensitivities are common in young people with autism – this varies and can include being under or over-sensitive to sound, smell, visual stimuli, touch and taste. Vestibular (balance) and proprioceptive (body awareness) difficulties are also common.

While it is difficult to turn a mainstream classroom into a completely low-arousal environment, teachers can be mindful of potential difficulties. Many young people with autism find it difficult to work in noisy classrooms, which are stressful and make it difficult to focus.

Smaller adjustments could include shutting the classroom door to block out corridor noise. Visual clutter should be reduced, messy classrooms are visually distracting and also reduce opportunities for independence – if the learning environment is structured and well organised then learners are able to collect and tidy their own equipment and resources.

We only use matt laminating pouches. Gloss lamination is reflective and can add to visual disturbance. As many young people with autism rely on visual support and prompts, it is important to ensure that they can see these clearly. Bright primary colours are not a good choice either – a neutral environment is preferable with pale blues/greens or natural furnishings such as wood.

Support staff

Many young people with autism will have a learning support assistant (LSA) with them in lessons. LSAs can be an essential support to autistic learners. However, research has shown that LSAs can be a barrier to teacher and peer interaction. Adults in the classroom should be mindful of this and ensure that support is targeted to the young person’s needs, rather than having an adult “stuck” to the young person. LSAs are often more familiar with the pupil and their needs but teachers should endeavour to build their own relationship with the young person too. Independence is an important skill. Autistic learners can be prompted to collect their own equipment and resources and natural interaction with peers can be supported.

Visual support

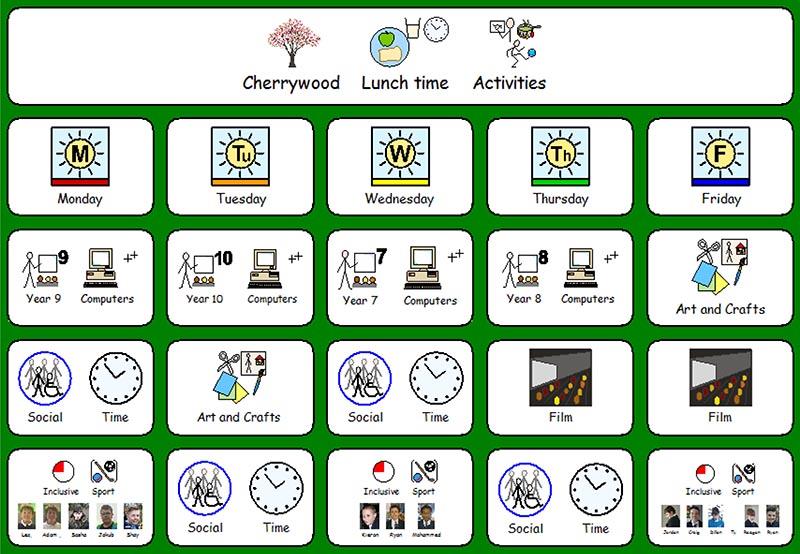

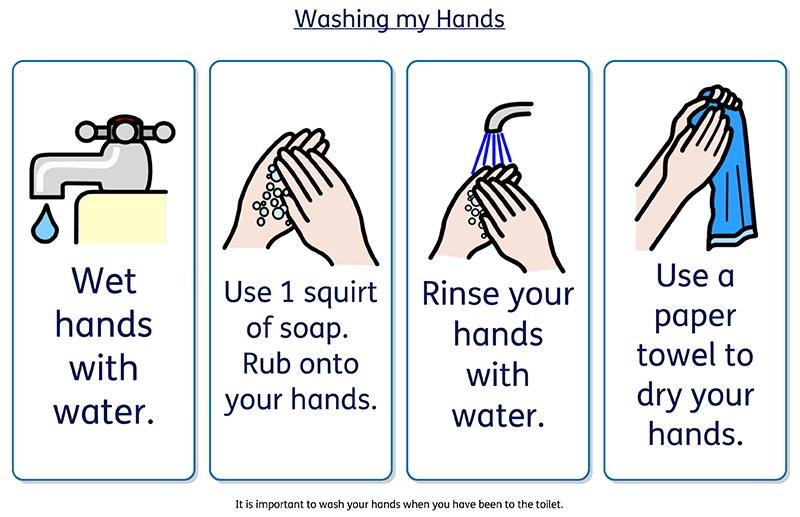

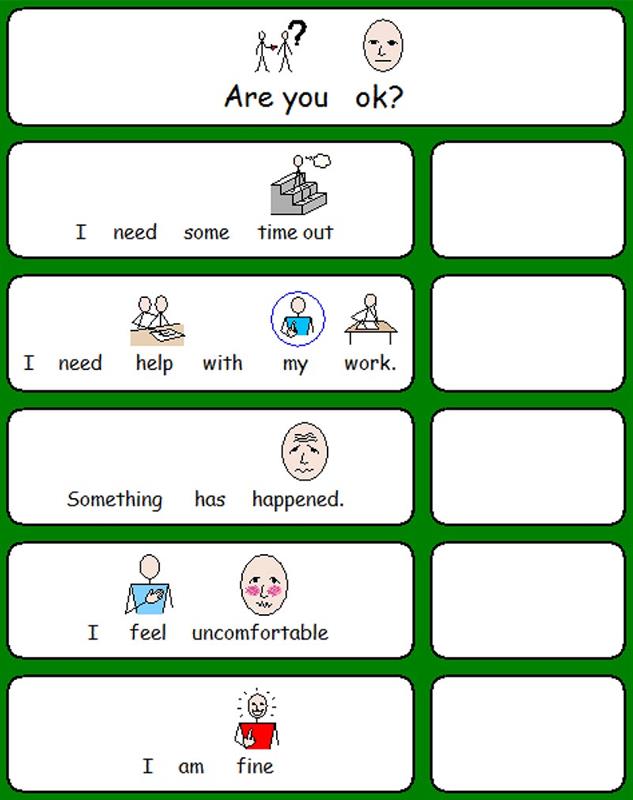

Most young people with autism are visual learners and effective visual supports and prompts (see example resources from Cherrywood, pictured here) can support a young person in understanding both academic and behavioural expectations.

Visual: Cherrywood Centre resources created by Janice March using Widgit Symbols (Credit: Widgit Symbols (c) Widgit Software (2016) www.widgit.com)

Visual supports also mean that information is available to the young person whenever they need it, increasing independence by reducing the need to ask for reminders. In a mainstream classroom, the young person may not pick up on whole-class instruction or may have difficulties in processing and retaining instructions. A written checklist is something concrete to refer to.

Visual supports can be adapted to the young person’s level of ability and comprehension. Many young people can also find comprehension difficult and depending on ability, it may be appropriate to use symbols or pictures to support written instruction.

Young people with autism often like to know what they have to do, for how long and what it will look like when they are finished. If this is not clear the task can appear open-ended and confusing. Checklists can be helpful with this. Some autistic learners have difficulty in expressing needs verbally, particularly when emotionally heightened or anxious. A visual or written prompt can provide structure to support expression.

Trips and visits

Many young people with autism can feel anxious about trips and visits. What will happen? How will they get there? Where will they eat lunch? Will it be noisy? Having this all written out in advance, on something permanent can reduce anxiety.

Social stories and visual supports are also useful in preparing young people for new or unfamiliar events or occasions. It can also ensure that rules and behavioural expectations are clear in advance of the visit and can be referred to throughout the day.

Help with behaviour

It is essential that young people with autism are taught the skills that they will need in their adult lives. Behaviour that may seem sweet or quirky when a child is small may get them into trouble as an adult. For example, many children with autism have preferences for particular sensory input – for example stroking hair or liking to feel tights. Such sensory preferences should be discouraged and redirected – could the child have a small piece of fabric to keep in their pocket instead?

Kari Dunn Buron and Mitzi Curtis have developed a five-point scale to explain behaviour (The Incredible 5-Point Scale, AAPC Publishing, 2012). I have used this in an adapted resource at Cherrywood as follows:

- Very informal social behaviour.

- Okay behaviour.

- Odd behaviour.

- Scary behaviour.

- Physically hurtful or threatening behaviour.

This initially can seem quite difficult a concept for some young people but is effective with learners of a wide range of ability and understanding. Level 5 behaviour is not acceptable under any circumstances and it is important that young people with autism learn that it is not okay to hurt someone – regardless of circumstance.

When a young person is angry, distressed or emotionally unsettled, it is easy to want to jump in and find out what happened. This can result in the young person being overloaded verbally or surrounded by people – often escalating the situation. It is important that, having made sure that the young person is safe, they are given some quiet time.

Social skills lessons can address social behaviour and young people with autism benefit greatly from social skills and PSHE lessons. These may need to be more direct and explicit than they would typically be with mainstream pupils.

Addressing challenging behaviour

When there have been times that a behaviour is unacceptable, it is important that the young person is debriefed afterwards and supported in understanding what went wrong and what they could do differently next time. As most young people with autism are visual learners, this is most effectively done with social stories and/or comic strip conversations.

There is no “one-size-fits-all” – sanctions should always be based on education: why did the pupil behave in this way and what will prevent them from behaving in this way in future. It is important to consider the motives behind the behaviour and this can only be done well when staff have a good understanding of the pupil. Reasons for challenging behaviour can be complex and at times detective work is required to spot a pattern. As autistic pupils can struggle with theory of mind, some may not see the relevance of sharing information, assuming staff already know that “x” took their pen or that they don’t like the noise of a particular machine in design technology.

Break and lunchtimes

Unstructured time can be a very difficult time of day for young people with autism. Ideally there should be access to a supervised area which is quiet. Some young people with autism can find it very difficult to know what to do with free time, needing guidance and predictability.

Young people with autism may need support and modelling of appropriate social behaviour. As generalising skills can be problematic, it should not be assumed that explicit teaching of social behaviour in a classroom will then be put into practice at social time. Supportive peers may act as good role-models, with adult supervision for more vulnerable autistic pupils.

Some young people really need structure to be added to lunch and break times and this could be done in the form of a written or visual timetable for lunchtime activities. At times, some students may need even greater structure than this, in the form of an individualised timetable.

- Janice March is the manager of the Cherrywood Centre at Benfield School in Newcastle upon Tyne. The Cherrywood team was the national winner of the Award for Inspirational Education Provision – Secondary and over 16 at this year’s Autism Professional Awards, run by the National Autistic Society. Visit www.autismprofessionalsawards.org.uk